On 6 June 2014, the Kuwait pavilion at La Biennale di Venezia’s 14th International Architecture Exhibition opened with a restaging of an event that took place three decades earlier: the ceremonial opening of the Kuwait National Museum. Under the heading “Acquiring Modernity” (responding to the overall Biennale theme “Absorbing Modernity”), the Kuwait pavilion seeks to “articulate the nation’s history of modernization” by focusing its participation on the history of the national museum, first established in 1957 and then re-opened in 1983 in a structure designed by French architect Michel Ecochard (figure 1).

According to the curator, Alia Farid, the team’s objective is to “[investigate] the repercussions of commissioning architectural works towards the formation of the State.” After the launch of Kuwait’s oil industry in 1946, the old port town was systematically demolished to make way for a new modern city. Throughout the ensuing decades, and particularly after the 1973 oil boom, the Kuwaiti government commissioned world famous architects to transform their new capital city into a symbol of the country’s prosperity and progress (what I have elsewhere called “Kuwait’s Modern Spectacle”). All of this was done with next to no public input or participation, and with little concern over how top-down urbanization would impact the everyday lives of the population.

[

[

[Figure 1: Michel Ecochard’s Kuwait National Museum. Source: Aga Khan Trust for Culture (photo by Michel Ecochard, with permission).]

The Pavilion

The aim of the Kuwait pavilion is to assess the impact of this planning paradigm by critically appropriating the themes of the Kuwait National Museum. Ecochard’s museum compound was divided into five main buildings: Administration and Cultural Section, Land of Kuwait, Man of Kuwait, Kuwait of Today and Tomorrow, and Planetarium. The pavilion team arranged the information they compiled after nearly a year of research around these five themes in an Acquiring Modernity pavilion booklet. According to the curator’s statement, “Ambiguous in what they are meant to convey, the themes are testament that any attempt to establish order without the involvement of the communities being served can only ever succeed as a folly. The reclamation of the themes is an effort to generate meaning and restore a sense of ownership and feelings of responsibility over Kuwait’s built environment.”

Restoring a sense of ownership over Kuwait’s built environment is a tremendous endeavor in a country, and a region, where urban planning and development are entirely the purview of the state and commercial elite. The research the team did in the months leading up to the opening was substantial. They uncovered a plethora of documents, plans, photos, and information that piece together the story of Kuwait City’s spatial transformation since the advent of oil. Nonetheless, several missed opportunities can be identified in the pavilion’s interpretation and showcasing of the nation-state’s experience of modernity.

[Figure 2: The Kuwait Pavilion in the Arsenale during the public opening on 7 June 2014. Photo by Roberto Fabbri.]

The pavilion space was transformed into a quasi-replica of the museum compound (figure 2). Aside from a brief introductory statement on the wall, there is little information or explanation within the space itself. The pavilion publication is where all the research and analysis is provided (but if you do not know the booklet is there, you may miss it). Though it is a pleasantly serene space in an exhibition that hits you with an overwhelming amount of information at every turn, after spending time there during the opening I could not help but feel like something was missing. The architecture biennale is not just about aesthetics, it is about sharing information, history, research, and analysis. A minimalistic approach can certainly be effective, but not to the point of emptiness. The Kuwait pavilion is situated on a corner of the Arsenale, with one entry opening onto a main corridor of country pavilions and another onto an outdoor courtyard area (and a café). Foot traffic is therefore guaranteed. And yet, except during the opening ceremony, the pavilion barely had any people in it during the otherwise crowded opening weekend (figure 3).

[Figure 3: The Kuwait Pavilion on 8 June 2014. Photo by Sharon Lawrence.]

But I am not an architect, nor am I a curator. Putting aside any misgivings I had about the execution, my main reaction to the Kuwait pavilion relates to the overall discourse associated with it (discourse that my own writing contributes to, as I wrote the introduction to the Acquiring Modernity booklet). My first concern (and this may sound bizarre considering the subject matter) is the team’s sole focus on architecture in unpacking Kuwait’s modernity. The second is the tension between the call to preserve Kuwait’s modern era and the nostalgic narrative of loss for Kuwait’s pre-oil past that permeates the publication essays.

Modernity Beyond Architecture

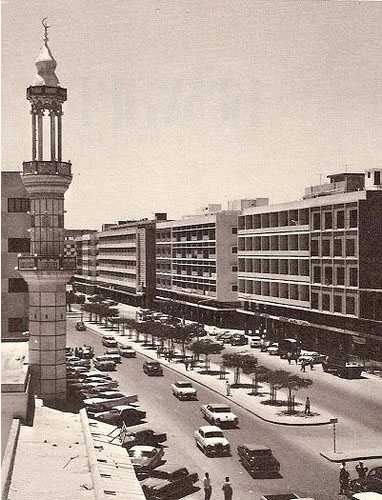

The Kuwait pavilion is above all a critique of state planning practices; as Farid puts it, “It is about questioning direction from those positioned above us.” Another of the team’s stated goals is to “[investigate] the impact of modernity on local culture.” However, there is very little in “Acquiring Modernity” that goes beyond defining Kuwait’s modernity and culture by its early oil landscape (Arne Jacobsen’s Central Bank, Malene Bjørn’s Kuwait Towers, and so on). Modernity was never just a physical landscape; it was an experience and a way of life. Kuwait’s modern era was not only defined by its iconic buildings, or by the negative effects of its modern planning practices (which were largely universal). As discussed during Art Dubai’s Global Art Forum 8 in March 2014, this was a period of excitement, flux, confidence, and change. It was a time when Kuwait’s education system was one of the best in the region, when women were burning their abayas to demand equality, when local arts, music, and theater were thriving, and when Kuwait’s democratic institutions were established. All of these were reflected in the landscape produced at the time (figure 4), but few of these markers of Kuwait’s modernity made it into the “Acquiring Modernity” discourse. Indeed, the phrase “acquiring modernity” implies that modernity was bought, imported, foreign (I will come back to this later).

[Figure 4: Fahad al-Salem Street in the early 1960s, showing Kuwait’s new modernist architecture. Source: Kuwait Oil Company.]

Yes, this is an architecture exhibition. However, the cleverly-appropriated themes of the museum compound gave the team opportunities to link Kuwait’s modernist architecture with the society, politics, and culture of that era: the realms where a country’s “modernity” (or lack thereof) is negotiated. Even the essays on “Administration and Cultural Section,” “Man of Kuwait,” and “Kuwait of Today and Tomorrow” focus predominantly on architecture and urban planning. In so doing, the pavilion, perhaps inadvertently, echoes state discourse and ideas about modernity in the early oil era which it is meant to be critiquing: that modernity was fundamentally something to be created/found within the bricks and mortar of the built environment. There is little critical analysis of what this urban landscape represented or how it impacted socio-political dynamics, nor of what it meant to “be modern,” for good or for bad, in Kuwait (and around the world) during this period. The only discussion of modernity’s impact on local culture beyond architecture is how oil transformed Kuwaitis from producers to consumers, or suburban shoppers. But suburbia and consumerism were both considered universal symbols of the modern ideal in the 1950s, so where did this fit within Kuwait’s own interpretation of what it meant to “be modern”? By restaging the opening of the Kuwait National Museum, the pavilion recreated the spectacle of Kuwait’s modernity without really saying much about it.

The reason I see this as a lost opportunity is because, as I discuss in the publication’s introduction, that era is all but forgotten in Kuwait today, where Islamic conservatism, intolerance, and xenophobia have stamped out all traces of what once made Kuwait “modern.” I do not mean to glance back at that era with rose-tinted glasses. Many of the seeds of today’s problems were indeed sown during Kuwait’s so-called “Golden Era:” the nationality law of 1959 which severely limited access to Kuwaiti citizenship; state crack-downs on political freedoms that same year in response to the pro-Nasser stance of Kuwait’s Arab nationalists (the first of many political crack-downs to come); the government’s mass naturalization of tribes from Saudi Arabia in the late 1960s in exchange for political loyalty; and so on. However, these are the aspects of Kuwait’s early oil decades that are most often remembered in present-day political discourse. The more exciting cultural traits I mentioned earlier are largely forgotten.

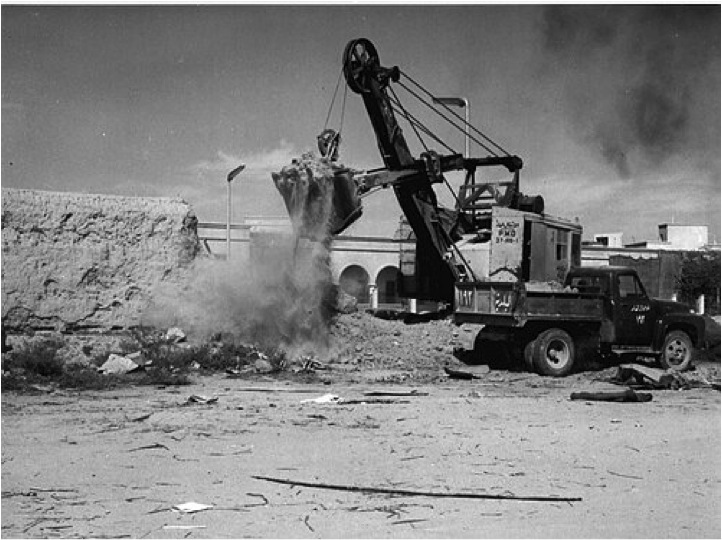

As a parallel process, the modernist landscape that represented in spatial form the excitement and confidence of that era is also being systematically demolished. In fact, the Kuwait pavilion constitutes part of a growing call to preserve the country’s modernist architecture; as Zahra Ali Baba of the National Council for Culture, Arts, and Letters wrote in the Acquiring Modernity commissioner’s statement, there is an “urgency of keeping alive evidence of Kuwait’s early modern era expressed through the physical landscape.” The pavilion thus aims to “raise awareness concerning the value of the modern city.” The reassessment, documentation, and preservation of modernist architecture is not unique to Kuwait; it is of course the theme of this year’s entire Biennale, and has also been spearheaded by groups like Docomomo internationally, and the Arab Center for Architecture regionally. The movement has been gaining momentum in Kuwait thanks to the initiatives of local architects like Zahra Ali Baba and Deema al-Ghunaim, among others. Just one month prior to the exhibition, Kuwait witnessed its first ever anti-demolition demonstration, protesting against the razing of the iconic modernist Chamber of Commerce building (which is now gone, figure 5). I have personally championed the call to stop the destruction of Kuwait’s modernist landscape since this process began in earnest in the mid-2000s. However, as I wrote in the introduction, “It is not just about the actual spaces, nor about fetishizing the past as we do with heritage [sites]. It is about remembering what those spaces once stood for, and what they signify about us as a society.”

[Figure 5: Architect Deema al-Ghunaim speaking at the protest against the demolition of the historic Chamber of Commerce building on 7 April 2014. Photo by Farah Al-Nakib.]

Modernity’s Paradoxes

This leads to my second observation about Acquiring Modernity. There is an underlying paradox running through the publication. On the one hand, there is a clear call to protect and safeguard Kuwait’s modern architecture. Hassan Hayat, in his essay on “Kuwait of Today and Tomorrow,” says, “It would cause great remorse to see the buildings of this era demolished; as artefacts of Kuwait’s ‘Golden Age,’ an effort must be made to preserve them before they too, are replaced.” On the other hand, much of the language that describes Kuwait’s modernization in the publication is one of loss. Some examples: “Acquiring Modernity is . . . an examination of the devastating side of affluence: it is a critical commentary on how, with the advent of oil, sensitivity and all sense of urgency was lost” (Farid). “Rapid change fragmented the social fabric as the normal associations, subcultures, and memories that formed the old city were erased” (Hayat). And finally, “[Kuwaitis] embraced modernity and welcomed a massive destruction [sic] of the old town without fully understanding its meaning” (Sara Saragoça Soares). Like many critiques of modern urban life, these sentiments, as Ash Amin and Nigel Thrift put it, “tell a story of an authentic city held together by face-to-face interaction whose coherence is now gone. If the authentic city exists, it is as a mere shadow of itself, one that serves only to underline what has been lost. In the great accounts of history, the modern city is more loss than gain.”[1] It is difficult to therefore ascertain what the pavilion is saying about Kuwait’s modernity: is it something positive worth protecting and remembering, or something negative that “destroyed” Kuwait’s more “sensitive” and “normal” pre-oil past (to use the publication’s own aforementioned language)? The reality is that modernity embodies this contradiction and is, of course, a bit of both. But again, there is little critical analysis of this. Instead, the pervasive narrative of loss inadvertently echoes present-day forces that have no qualms about demolishing Kuwait’s modernist landscape because, as one man working in the heritage industry told me in 2009, “They don’t represent our heritage.”

Interestingly enough, this tension of simultaneously reifying and vilifying the past is inherent in the Kuwait National Museum itself. When it was established in 1957, the museum’s aim was to capture snapshots of a life rapidly disappearing outside its doors. At the same time, Ecochard’s 1983 building was one of the symbolic structures meant to deliberately replace Kuwait’s pre-oil past with a spectacle of modernity. The building was therefore complicit in erasing the past it was designed to exhibit. Furthermore, by their very nature museums are tools of modernity, insofar as they bring rationality, order, and function to the everyday chaos of history. The museum was therefore an excellent choice of structure on which to base the pavilion, as it perfectly represents the inherent contradictions of modernity and its relationship to the past (and, through the team’s present-day intervention, the future). But it was also a curious choice of structure for the pavilion to “keep alive evidence of Kuwait’s early modern era,” seeing it was built to house memories of Kuwait’s pre-oil past. Either way, there is little discussion anywhere in the literature surrounding the pavilion as to why the team focused on the museum, once again reflecting a lost opportunity for critical discourse.

It is undeniable that modernity had a destructive side in Kuwait—as everywhere else in the world—wiping out much of what came before (figure 6). But, as already discussed, that is not all that Kuwait’s modern era was about. Nor was modernity entirely brought in by foreign consultants. In her essay “Monologues with Bureaucracy” (which falls under the “Administrative and Cultural Section”), Dana al-Jouder claims that, “Kuwait sought foreign consultants to tell us how to be modern: what we had to display, how we had to behave, live, and function.” In continuing her aforementioned explanation of “Acquiring Modernity” as an examination of the devastating side of affluence, Farid goes on to say that the theme also “suggests a learning curve . . . acquiring an understanding.” Though offering a more sympathetic side to the story, this suggests that Kuwaitis had to learn how to be modern. This idea, coupled with the narrative of loss just described, too easily, albeit unintentionally, plays into the hands of present-day critics who argue that modernity was a foreign (read: Western) concept that should be erased, and that Kuwait should go back to its more traditional (read: Islamic) roots.

[Figure 6: The destructive side of modernity: demolishing old Kuwait Town in the 1950s. Source: Kuwait Oil Company.]

In terms of architecture and planning, the work of one of Kuwait’s most significant early oil planners, the Palestinian-American Saba George Shiber, challenges the local/foreign and tradition/modernity dichotomies emphasized in present-day discourse. When he joined the Kuwait Municipality in 1960, Shiber was immediately critical of the Western planning experts he felt had disrupted Kuwait’s historic urbanism in the first decade of oil. However, as an architect and planner he did not fetishize the past or aim to excavate a “traditional” Arab identity stamped out by European modernity. Rather, in planning Kuwait City’s central business district in the heart of the historic commercial center, Shiber reached into Kuwait’s past to show that the pre-oil city had a logical organization that could be relevant to the present and serve as a suitable inspiration for a modern urban order. For instance, he promoted the practical rather than decorative application of local architectural styles like shaded and colonnaded liwāns and mashrabiyya window coverings, which were then used to create some of Kuwait’s most iconic modernist structures in the CBD like Dar al-Handasah’s now-demolished Chamber of Commerce building mentioned above. Shiber’s CBD shows us that Kuwait’s modernity was not just an imported foreign concept but something that could also be derived from its own pre-oil past.

Being “Modern” in Kuwait

Being modern in Kuwait in the early oil decades did not just mean being a pantheon of modernist architecture, or being a society of suburban consumers. Above all, it meant being open to the world and to new ideas, new influences, and new ways of living. This was a modernity that was not acquired: it had its roots in Kuwait’s port city past. Kuwait had always been a tolerant, hybrid, and cosmopolitan society that picked up cultural influences from the Indian Ocean port towns it came into contact with through shipping and commerce. After oil those cultural influences shifted west to the Arab world, Europe, and the United States. Under the guise of change, this reflects continuity with Kuwait’s pre-oil past. Again, there was a lost opportunity to unpack this a bit more: to examine Kuwait’s modernity as continuity rather than solely as rupture, in order to give it greater legitimacy in present-day discourse. This, more than anything, could help raise awareness on the value of the modern city and of Kuwait’s modern era more generally.

Despite these shortcomings in the execution and discourse of the Kuwait pavilion, there are ways in which the team itself vividly captures and represents Kuwait’s “modernity.” First and foremost, it was a hybrid team, consisting of twenty-three Kuwaitis and non-Kuwaitis of mixed backgrounds, reflecting the cosmopolitanism that the country’s modern era was so famous for and that in the post-invasion decades has been replaced by rampant xenophobia (figure 7). It was also a young team, with an average age of thirty-one. They remind us of the pioneers of the early oil era: the young men and women who felt they had a real stake in Kuwait’s modern development. Active youth participation in all areas of development has been missing in Kuwait for decades but slowly seems to be returning, and the Biennale team certainly reflects this.

[Figure 7: Part of the “Acquiring Modernity” team during the opening ceremony on 6 June 2014. Photo by Farah Al-Nakib.]

Finally, “Acquiring Modernity” is fundamentally a bottom-up critique of Kuwait’s decision-makers, a questioning of authority that has been an inherent part of Kuwait’s political landscape since well before the coming of oil, formalized in the early 1960s in those modern symbols of democracy: the Constitution and Parliament. Freedom of expression and a relative balance of power between the rulers and the ruled have always set Kuwait apart from its Gulf neighbors. At the peak of Kuwait’s early oil era, its press was described as one of the freest in the world. It is not surprising, then, that the pavilion is a thoughtful critique of Kuwait’s modernization rather than a celebratory display of the country’s achievements. This also sets it apart from the nearby United Arab Emirates and Bahrain pavilions.

The latter spaces were actually two of my favorites in the entire Biennale. They contain what the Kuwait pavilion is missing: interesting and informative displays that make you spend time interacting in and with the space. But they lack what, to me, best defines the Kuwait pavilion: critique combined with locality. The UAE pavilion, entitled “Lest We Forget: Structures of Memory in the United Arab Emirates,” is curated by Dr. Michele Bambling, assistant professor of art history at Zayed University, along with three colleagues. The pavilion is an archival display of the United Arab Emirates’ architectural and urban development, with little critical assessment of this development. The Bahrain pavilion, titled “Fundamentalists and Other Arab Modernisms,” actually has nothing to do with Bahrain specifically and is curated by two of the Arab world’s most prominent figures in architecture: Bernard Khoury and George Arbid, both from Lebanon. Kuwait’s pavilion, by contrast, is an “obsessively local” (as Farid puts it) project put together by an eclectic group of Kuwait’s “urban citizens”—city users of all nationalities—to generate a critical, interdisciplinary discussion on Kuwait’s urban development practices: the good (the beautiful water towers that puncture the Kuwaiti landscape), the bad (the “bureaucratic orgy” of the state planning apparatus that results in delayed construction), and the downright bizarre (a woman’s bathroom door in Jacobsen’s bastardized Central Bank “with a handwritten sign that protrudes awkwardly into the banking hall”). In this, the Kuwait pavilion takes a significant step in achieving one of its goals: restoring a sense of ownership and responsibility over Kuwait’s built environment.

“Acquiring Modernity” is not over yet. While the Biennale remains open until late November, the Kuwait team is also currently working on a film project in conjunction with the pavilion. Most importantly, the team has made a substantial contribution to an emerging national dialogue about Kuwait’s urbanization, modernity, and modern heritage that will continue even after these particular projects end. The missed opportunities mentioned above may therefore be realized soon enough.

--------------------------

[1] Ash Amin and Nigel Thrift, Cities: Reimagining the Urban (Malden: Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 2007), 32.

![[The Kuwait Pavilion in the Arsenale during the public opening on 7 June 2014. Photo by Roberto Fabbri.]](https://kms.jadaliyya.com/Images/357x383xo/farahcover.jpg)